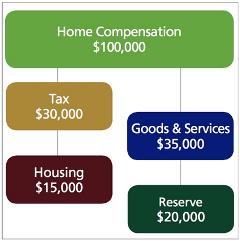

OK, so you read through my first brief on Expatriate Payroll Tips in the last issue and are wondering, where should I begin? I suggest the first stop on our expatriate payroll tour should be to develop an understanding of the core of most expatriate policies—the balance sheet model. This is a structure of policies that support the vast majority of international expatriate assignments. Indeed it may be poorly named, as the expat balance sheet has nothing to do with accounting, but instead the balance sheet starts by splitting an employee’s compensation into four parts, which reflect what they are used for. The four parts are:

OK, so you read through my first brief on Expatriate Payroll Tips in the last issue and are wondering, where should I begin? I suggest the first stop on our expatriate payroll tour should be to develop an understanding of the core of most expatriate policies—the balance sheet model. This is a structure of policies that support the vast majority of international expatriate assignments. Indeed it may be poorly named, as the expat balance sheet has nothing to do with accounting, but instead the balance sheet starts by splitting an employee’s compensation into four parts, which reflect what they are used for. The four parts are:

- Tax

- Goods and services

- Housing

- Net reserve

Figure 1 shows what an employee earning $100,000 per year might spend on these various components.

A balance sheet policy will provide additional allowances to ensure that, at the end of the day, employees are walking away with the same reserve that they would have had if they had remained at home.

Balance Sheet Allowances, Tax

Balance Sheet Allowances, Tax

If additional cash is needed in the assignment location to purchase the same set of goods and services that the employee would purchase at home (think “How much does an apple cost in New York City versus Paris?” or “How much is a movie in San Francisco versus Tokyo?”), then an allowance is provided for an under-the-balance-sheet model. The same is true for housing. Each allowance provided must be considered for a “tax gross-up” (tax and the tax on the tax) or the employee will have to pay for the tax on the additional allowances out of his or her net reserve. So it is likely that if there are allowances for housing and goods and services, the tax cost will be higher as well, and the employer, therefore, will have to pay the gross-up if the reserve is to remain intact (see Figure 2).

In this case, after the additional $10,000 of cost-of-goods allowance and $15,000 housing allowance, the employer must fund an additional $20,000 for the tax gross-up so that the employee maintains the $20,000 reserve.

Policies address these allowances in many ways. For example, the differentials can be paid in cash, and housing can be delivered as a benefit in kind with the employer paying the rent in the local currency.

Often, companies running a balance sheet model will retain an amount equal to what would have been the stay-at-home tax. This retention is called “hypothetical tax.” Retaining hypothetical tax from the expatriate ensures the employee pays his or her fair share of tax. In return for the hypothetical tax, the employer pays all of the actual expatriate tax obligations—both at home and abroad. In the case above, the employer would have retained $30,000 in hypothetical tax from the employee and paid $50,000 of actual taxes. Net cost to the employer is $20,000 in this example.

Often, companies running a balance sheet model will retain an amount equal to what would have been the stay-at-home tax. This retention is called “hypothetical tax.” Retaining hypothetical tax from the expatriate ensures the employee pays his or her fair share of tax. In return for the hypothetical tax, the employer pays all of the actual expatriate tax obligations—both at home and abroad. In the case above, the employer would have retained $30,000 in hypothetical tax from the employee and paid $50,000 of actual taxes. Net cost to the employer is $20,000 in this example.

As you can see, processing payroll for balance sheet expatriates is complex. It requires special pay codes to properly report balance sheet items, including hypotheticals. Because two payrolls are running simultaneously (a home and host payroll), close coordination is needed to ensure all earnings and deductions are properly reported and updated where required to the other payroll. There also needs to be a means to prevent either payroll from duplicating the payment of compensation or expatriate allowance.

To sum it up, the balance sheet is the policy structure employers use to protect an employee’s reserve. It provides allowances where the assignment costs exceed those at home, and then covers the tax on those allowances to ensure the employee is not out of pocket for housing, living costs, or tax.

I will discuss more about the balance sheet and pay code strategies in future tips.