Recently, I presented a webinar with the Global Payroll Management Institute (GPMI) on the topic of shadow payrolls. I discovered that although shadow payrolls are not well understood, the global payroll community has a strong desire to learn more about them.

Recently, I presented a webinar with the Global Payroll Management Institute (GPMI) on the topic of shadow payrolls. I discovered that although shadow payrolls are not well understood, the global payroll community has a strong desire to learn more about them.

Not long ago, I found myself in a conversation with a manager of U.S. payroll for a well-known international company. She said it seems to take 20 times the effort to process a payroll for one of their 300 expatriates than for any of their 60,000 other employees. Whether a factor of 10, 20, or 100, it seems whenever the topic of expatriate payrolls come up, eyes roll, stories pour out, and you can feel a certain pain that anyone who has managed expatriate payrolls knows well.

The focus of this two-part article will cover these main pain points:

- What makes payroll for expatriates so hard to process?

- Can the complexity be explained?

- Can it be simplified?

Understanding Shadow Payroll Complexity

Two attributes are responsible for shadow payroll complexity and the corresponding frustrations for payroll processors.

The first complication relates to international assignment policies, which gets to why we are doing this in the first place. Expatriates are covered by mobility policies meant to address important concerns such as:

- Taxes

- Cost of living

- Housing

- Foreign exchange

- Other moving expenses, even the question as to whether an employer will pay for relocating pets

These policies are often designed by human resources professionals trying their best to be fair—to the employee and employer. But when putting these policies together, the last thing HR is thinking about is how they will be reflected in payroll.

Payroll staff, who are tasked with processing expatriate payrolls that need to interpret and reflect these policies, are often unfamiliar with the logic of the transactions they are being asked to administer.

There is no context for them to work with, so setting up the pay codes and executing the transactions is like putting a bicycle together from its pieces without knowing exactly what it is supposed to look like at the end.

Second are process complications.

Because expatriates are often on both home and host payrolls at the same time, there is a need to coordinate a regular exchange of payroll information between two countries.

Each period earnings, deductions, and taxes must be properly reported:

- On two payrolls

- In two currencies

- Often at two payroll frequencies

- While ensuring that net pay is delivered timely and accurately

This requires a solid understanding of what should be reflected on each payroll, what to gross up, and which payroll is delivering each element of compensation or benefit.

All of this needs to be managed according to the rules of home and host law, as well as company mobility policy and accounting protocols.

What follows will shed light on these two aspects of expatriate payroll. However, it is only a starting point, as there are all kinds of variations on the themes presented. I’ve chosen to use a U.S. outbound expatriate program for purposes of my illustrations, as I expect that the readers of this article are primarily U.S. payroll professionals.

Basic Understanding of Expatriates

In order to begin to break down expatriate program policy logic and explain the basics of the underlying payroll processes, let’s start with three quick definitions:

Shadow Payroll—When an employee transfers abroad on an expatriate assignment from the United States, shadow payroll refers to the host country payroll and is primarily used to report earnings, deductions, and taxes in the host location currency. It may deliver local allowances (such as cost-of-living allowances), but it generally does not deliver net pay to the employee. This is done via the home (U.S.) payroll.

Expatriate—As relates to this article, an expatriate:

- Is an employee who is transferring on a long-term assignment from the United States to another country

- Is covered by a company-sponsored mobility policy

- Remains on the U.S. payroll in addition to the shadow payroll throughout the duration of the assignment

Long-Term Assignment—A long-term assignment is one that will last long enough that payroll reporting is statutorily required in the host country (you can assume longer than six months) and the assignment is not indefinite (i.e., the employee is not taking up a permanent residence in the host country).

I want to hit the pause button here. At this point you might be asking yourself, “Why do we have to report expatriates on two payrolls in the first place? Wouldn’t things be so much simpler if we could just pay them out of one—the United States or the host country—rather than both?”

The answer is, “Absolutely yes.” It would be much simpler to pay an expatriate out of one payroll. But there are good reasons that expatriate payrolls are often structured as split payrolls.

Consider first that an expatriate usually expects to return to the United States after a couple of years. Therefore, the expatriate would likely want to remain tied to U.S. FICA and Medicare programs and, possibly, maintain their participation in certain U.S. benefits such as a 401(k) plan. Additionally, there may be U.S. equity or bonus programs that the employer wants the employee to participate in that may not be available if the expatriate is employed solely in the host country. And our long-term expatriate is almost always a tax resident and required to be reported on the host country payroll in the same way that you can’t just transfer a German national to work in a U.S. subsidiary and pay them out of Germany without legally setting them up on a U.S. payroll as well while they work in the U.S.

These ends can only be achieved if the expatriate is reported on the home (U.S.) payroll in addition to the host payroll.

Assuming, then, that a split payroll is the preferential structure for an expatriate employee, let’s look at the basics of global mobility policy and consider how it will affect the setup of U.S. and shadow payrolls through this lens.

The Balance Sheet Model

Although there is an endless variety of ways to do it, a common approach for developing expatriate policies is referred to as the balance sheet model. To be clear, the balance sheet has absolutely nothing to do with accounting.

Instead, it refers to a method that addresses four specific factors of economic life while an expatriate is on assignment and how, through a series of allowances, those factors can be “balanced” in a way where the expatriate’s net pay and quality of life can be protected.

The four economic factors are:

- Housing

- Cost of living

- Tax

- Net reserve

The theory is that any employee receiving compensation spends it on the first three factors leaving the fourth, net reserve for things like savings, retirement plans (including 401(k) and social security), or other personal, non-essential purchases like hobbies.

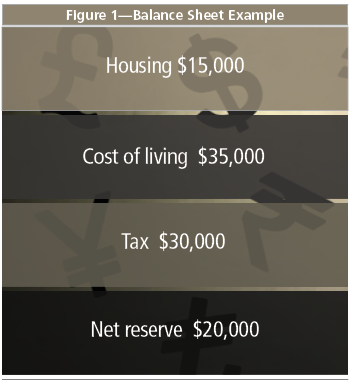

The balance sheet theorizes that for any combination of salary, family size and status, and home location, a theoretical housing, cost-of-living, and tax cost can be determined, leaving a specific net pay that the employee would have been receiving at home. Figure 1 shows an example I used in my recent webinar for an individual earning $100,000.

Figure 1—Balance Sheet Example

The balance sheet model suggests that when the expatriate goes on assignment, they would be concerned that:

- Their net remains the same ($20,000)

- Their quality of life remains consistent

Let’s think about this for a moment. What if the employer reduced the amount paid to the employee via the U.S. payroll and only delivered the employee $20,000 net? And further, the employer agreed to provide appropriate housing to the employee in the assignment location, a cost-of-living allowance in an amount that would allow the employee to replicate his or her stay-at-home lifestyle, and also paid 100% of any tax (either in the U.S. and/or in the assignment country)? In that case, the employee’s economic life would be “in balance.” The employee would have the same net after tax in the bank while enjoying an equivalent housing and quality of life while on assignment. This is the basis of the balance sheet model.

In part II of the article, we will look at how the balance sheet model translates to the U.S. payroll structure and some best practices when it comes to shadow payroll.

Do you like our content? Join the GPMI community to get free education and articles straight to your inbox!

Dave Leboff has close to 40 years of experience in international human resources, international tax, and expatriate program management. He began his career in tax, working for the U.S. Internal Revenue Service and then for Arthur Young in New York City where he received his CPA and managed sizeable expatriate program engagements. Leboff moved to the client side and served in international assignment and global human resources roles at PepsiCo, Bankers Trust, UBS, and DoubleClick before forming Expaticore, which was acquired by Immedis in May 2017. Leboff is a recognized thought leader in the industry who has written numerous articles on international payroll and expatriate program administration. He regularly speaks at industry conferences in the U.S. and around the world covering a wide range of topics relevant to global workforce management. Leboff also serves as co-chair of the Global Issues Subcommittee of the Strategic Payroll Leadership Task Force (SPLTF) of the American Payroll Association.