India’s labor market is the second largest in the world, after China, with a working-age population of about 520 million people. In 10 years, it is expected to be the world’s largest as China’s population, aged 15 to 64, drops from 20.5% to 18.3%.

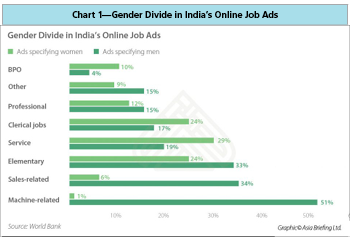

While this positive demographic growth should be advantageous for business, only a small portion of India’s working-age population is actually engaged in the formal workforce—the primary reason being that barely one in four women is part of the country’s workforce (see Chart 1).

Today, industry estimates show that women in India only make up 5% to 6% of directorships at most listed companies—this after amendments to the Companies Act mandated at least one woman be on company boards.

These figures underline the highly distorted nature of India’s labor market, where women hold 45% of university degrees but are either denied employment opportunities or experience much slower career growth trajectories due to gender-based discrimination (see Chart 2).

Chart 1—Gender Divide in India’s Online Job Ads

Chart 2—Ad-Specified Salaries Pay Women Less

Gender Parity for Inclusive Economic Growth

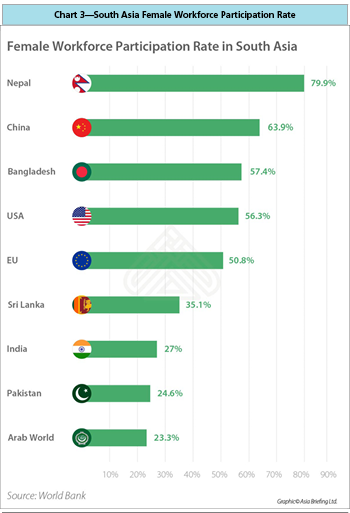

India has the lowest female labor force participation rate in its neighborhood. At about 27%, it falls well below Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Nepal (see Chart 3). While female employment is higher in rural India, it is mostly as underpaid and temporary labor, though even here the rate of participation is declining.

In a recent study, the World Bank noted that more than 21 million Indian women dropped out of the rural workforce between 2005 and 2012. On the other hand, only two million Indian women joined the urban workforce.

Recent labor data from a government survey dated 2015-16 reveals that women comprise only 16.2% of all urban workers and 26.7% of all rural workers. In 1972-73, Indian women comprised 13.4% of all urban workers and 31.8% of all rural workers.

To put this into perspective, the overall rate of female labor force participation declined as the Indian economy opened up, urbanized, and diversified with the growth of new industries, unlike most other regions in the world. In fact, rapid growth experienced by the United States and China in the past century illustrates how improving the gender balance in the workforce contributes to a nation’s economic growth. Female labor force participation is 56% in the United States and 64% in China.

The above correlation is also strengthened by a 2017 IMF study that states that increasing the female labor force participation will grow India’s GDP by an estimated 27%. Contrast this with the projections made by the government’s big idea reforms “Make in India” and “Digital India,” which aim to boost India’s growth by 16% and 5%, respectively.

Yet, GDP goals aside, the gender imbalance in India’s workforce stunts future prospects for inclusive growth in the country. It deprives women and girls of role models in the workplace, reduces their motivation to study further, and perpetuates unhealthy socio-cultural attitudes. Leaving out one half of the population from its workforce will also prolong India’s status as a developing country.

Chart 3—South Asia Female Workforce Participation Rate

Diversity Hiring Is Good for Business

Given the entrenched nature of India’s skewed gender ratios in the labor market, much needs to be done to enable greater participation of women. Limiting changes to satisfy legal compliance alone will be insufficient, if not counterproductive.

Balanced and fair recruitment practices, instead, will open up career growth opportunities for women, and remove the uncompetitive barriers that kill innovation, productivity, and enterprise.

Firms benefit when they view gender-positive hiring and promotion as a key cultural value. It incentivizes employees to take greater ownership of their work as fear of prejudice or harassment is reduced or removed. Fostering a positive work environment also enhances a company’s market image and increases its ability to attract the best talent and clients.

A 2014 study by MIT noted that bringing more women on board improves a firm’s profitability and can increase revenue by more than 41%. Another interesting study by the U.S.-based nonprofit Anita Borg Institute found that teams with more women showed greater confidence, psychological safety, group experimentation, team efficiency, and a lower turnover rate.

Even if the results seem forced, their explanation is simple—gender-balanced workforces bring in fresh and new perspectives and ideas. While the growing body of research underlines the positives of hiring more women, it also proves just how much firms—and countries—lose out when they don’t pursue inclusivity. If women constitute barely one-third of India’s workforce, that means many talents are wasted, people are left behind, and growth prospects are diminished.

Corporate India Catches Up

Multinational corporate firms in India are becoming more conscious of the need for diverse hiring practices. Initially compelled by government targets and client incentives, more Indian companies are willing to scout for female candidates and even pay more for female hires.

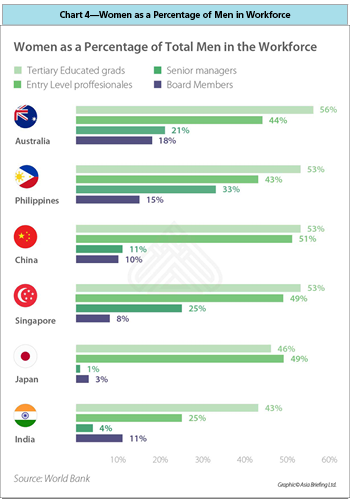

Talent strategy firms are increasingly consulted with respect to staffing more women. A 2018 global recruitment trends report showed that Indian recruiters led even Western countries when prioritizing diversity hiring policies. This is also the case for hiring women for top management roles and senior positions (see Chart 4).

Chart 4—Women as a Percentage of Men in Workforce

Noting the progressive trend, industry watchers insist that diversity must mean equality, not hiring more women to meet only specific roles or fill mandatory allocations. Firms keen on diversity hiring should advertise the job and not the candidate, use multiple hiring tools to attract greater interest, and shortlist candidates fairly to move beyond the usual recruitment pool. This means making diversity hiring an intent, and not merely a compliance-bound policy.

Further, young women who leave the workforce for personal reasons—family-related or otherwise—may find it difficult to regain employment. Discriminatory attitudes about candidates who have taken a sabbatical and invasive personal questions too often discount qualifications or experience relevant to the job advertised. Companies in India can prevent this by ensuring that diversity and inclusion policies are institutionalized.

Government Efforts to Reduce Disparity

India’s federal and state governments have mandated several laws to encourage female participation in the labor market and promote diversity. These hold importance as India is still a conservative country, and women constantly fight to overcome stigmas and sexist attitudes, both at home and in the workplace.

The Companies Act, 2013, forced companies to name at least one woman on the corporate boards of listed and certain other companies. This resulted in various superficial practices, such as director-in-name-only, particularly among the country’s family-run businesses that dominate India’s formal economy. However, many hope that over time, firms will adjust their hiring strategy with more diversified goals.

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act, 2013 seeks to protect women from harassment at the workplace and institutes safeguards. It applies to all government and private entities operating on a commercial basis, as well as work in education, entertainment, vocational services, sports facilities, health services, and any place visited by the employee arising out of or during the course of employment.

The Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act, 2017 provides women in the organized sector paid maternity leave of 26 weeks, up from 12 weeks, for the first two children and 12 weeks for the third child; 12 weeks of maternity leave for mothers adopting a child below the age of three months as well as those who opt for surrogacy. In other provisions, the law mandates that every establishment with over 50 employees must provide crèche (daycare) facilities within easy distance.

These important legal provisions seek to improve working conditions for women and encourage participation in the workforce. While the laws reflect core compliances for most businesses in the country, the private sector has many ethical and economic reasons to adopt best practices like gender balanced workplaces and safe working environments that actively seek to encourage workforce participation.

Do you like our content? Join the GPMI community to get free education and articles straight to your inbox!

This article was first published on India Briefing.

Since its establishment in 1992, Dezan Shira & Associates has been guiding foreign clients through Asia’s complex regulatory environment and assisting them with all aspects of legal, accounting, tax, internal control, HR, payroll, and audit matters. As a full-service consultancy with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, and ASEAN, we are your reliable partner for business expansion in this region and beyond.

For inquiries, please email us at [email protected]. Further information about our firm can be found at: www.dezshira.com.