The fact that Brazil has one of the oldest and most protectionist labor laws in the world poses some challenges to workers’ welfare. In 1988, Brazil adopted a new Constitution, which revised labor regulations that had been in place since the 1940s. The revised regulations aimed at improving employees’ welfare and offering them more protection and better working conditions.

Despite these new regulations’ original goals, employees’ welfare has not improved. On the contrary, a few people dare to say the prevailing Brazilian labor law actually harms workers´ rights instead of protecting them. In his book Politically Incorrect Guide to the Brazilian Economy, author Leandro Narloch draws a comparison between Brazilian labor legislation and the measures taken by governments to reduce the harmful consumption of tobacco and alcohol.

According to Narloch, in order to convince people to stop smoking, governments across the world raise taxes and regulate a minimum price for the purchasing of those substances. This creates an effect: in the long run, people reduce cigarette consumption and, as a natural consequence of such action, the cases of lung cancer and related diseases decline. Narloch also references a World Bank statistic that corroborates this thesis: in poorer countries, each 10% tax increase on tobacco products yields on average an 8% decrease in consumption.

While reading Narloch’s book, one might ask what the parallel is between cigarette taxation and labor legislation in Brazil. The answer is simple. The expected effect of tax increases is lower cigarette consumption. In Brazil, the same effect is observed concerning labor laws and employers: high and complex taxes discourage or render the labor contract unfeasible. The difference, however, is the government’s lack of intent to tackle this issue.

We can establish a comparison between the formal work relationship regulated by the labor code (we are going to refer to them as “CLT workers” for Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho, or Consolidation of Labor Laws) and the informal work relationship not regulated by the labor code (the non-CLT workers). The employers that hire non-CLT workers are not subject to some rules and taxes that apply only to CLT workers. This is the most relevant motive for discouraging emplyers from hiring a professional under labor rules in Brazil. To better explain this, let’s look at the rates, taxes, and indirect costs to which employers are subject under this type of labor contract (CLT work) in Brazil:

- Social Security Contribution —INSS (up to 28.8%)

- Unemployment Compensation Fund—FGTS (8%)

- Vacation pay (12.12% approximately)

- 13th month salary (9.09% approximately)

- INSS and FGTS on vacation pay and 13th month salary (7.79% approximately)

- Dismissal without good cause—the employer is liable to pay a penalty of 50% of the FGTS funds deposited in the terminated employee’s FGTS account

These taxes and rates were created after decades of military rule, as mentioned by Simeon Djankov and Rita Ramalho in their 2009 article in the Journal of Comparative Economics:

“These political changes brought about labor reform. It reduced the maximum working hours per week from 48 to 44 hours; reduced the maximum number of hours for a continuous work shift from 8 to 6 hours; increased the minimum overtime premium from 20 percent to 50 percent; and increased maternity leave from 3 to 4 months.”

The authors go on to say how the new Constitution changed the mandatory individual savings account system created in 1966. Prior to the reforms, the law required employers to deposit 8% of employees’ wages in a worker-owned account. Then in case of separation, workers could withdraw the accumulated funds (plus the interest). In addition, if a firm initiated job termination, it had to pay a penalty equivalent to 10% of the amount accumulated in the account. As part of the 1988 reform, this penalty was increased to 40%, considerably raising the cost of dismissing a worker. The authors state that similar reforms have taken place in Chile, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua, but in contrast, Colombia and Peru made labor regulations more flexible.

Many studies analyze flexible labor laws versus the decrease of unemployment rates. Narloch compares Italy’s labor legislation with the United States, indicating that Italy could decrease its unemployment rate from 8% to 5% were its labor regulations more flexible.

Narloch delineates an important comparison: if one may say the strictness of labor laws actually harms workers, it is necessary to prove workers have better living standards in countries that are more flexible when it comes to labor rules. To illustrate, the author divides some countries into two groups:

- United States, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong (China), Maldives, and the Marshall Islands

- Bolivia, Venezuela, Equatorial Guinea, São Tomé and Príncipe, Tanzania, Congo, and Central African Republic

Advocates of labor legislation would have the most stringent rules applied to group 1 (world’s richest countries). However, the most flexible legislation is placed on those countries included in group 1, where workers enjoy a better life (in terms of quality of life standards). The strictest labor laws are overwhelmingly applied to group 2.

This article does not intend to discredit all achievements made by Brazilian workers during their history. Its main purpose is to incite an economic analysis of the regulatory background of labor and social security laws and their impact on the current Brazilian economic scene. We hope to explain the complexity of Brazilian labor and social security laws that comprises not only the rigidity of labor rules but also the complex environment that surrounds the tax reports to the government.

Getting to Know Brazilian Labor Law, Payroll, and Social Security

As previously mentioned, Brazilian labor tax involves payment of the Social Security Tax, Unemployment Compensation Fund, and withholding income tax (IRRF) on payments made to employees. The employer is responsible for the calculation of the taxes, which typically uses the employee’s compensation.

As previously mentioned, Brazilian labor tax involves payment of the Social Security Tax, Unemployment Compensation Fund, and withholding income tax (IRRF) on payments made to employees. The employer is responsible for the calculation of the taxes, which typically uses the employee’s compensation.

According to the Brazilian legislation, in order to register payments on a monthly basis to employees and independent contractors, the employer is obligated to prepare a payroll for each of the company’s branches. It is important to stress that Brazilian companies rarely manage to record all the information about their independent contractors on payroll. A bigger challenge is to find companies that segregate their payroll by companies to which they render service. Using this information on the company’s monthly compensation of its workforce, the employer will be able to calculate most of the labor-related taxes.

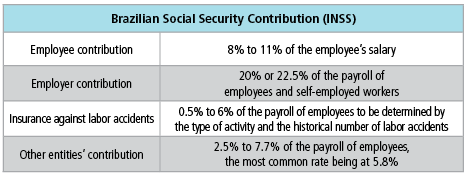

Brazilian Social Security Contribution (INSS) is composed of the following:

- Employee contribution (8% to 11% of the employee’s salary)

- Employer contribution (20% or 22.5% of the payroll of employees and self-employed workers)

- Insurance against labor accidents (0.5% to 6% of the payroll of employees to be determined by the type of activity and the historical number of labor accidents)

- Other entities’ contribution (2.5% to 7.7% of the payroll of employees, the most common rate being at 5.8%).

For employees whose work involves personal risk, the company must pay insurance against labor accidents under special conditions (6% to 12% of the payroll for employees working under these conditions). Under this scenario, the usual rate of an employer’s social security contribution is 28.8%. Besides this rate, the employer has the obligation to withhold 8% to 11% of the employee’s monthly salary (limited to Brazilian real (BRL) 608.44 per month) for the social security contribution.

The wrong perception of a company’s activities might result in a different social security contribution rate and consequently in overpayment or underpayment of the amount owed by the company. In this scenario, if a company has a tax assessment, the amounts involved tend to be significant, since the company will have to pay the difference between the tax rate used and the tax rate owed, plus a penalty (from 75% to 150%, in case of fraud) and interest.

Regarding the Unemployment Compensation Fund (FGTS), the employer is obliged to the monthly payment of 8% of the employee’s compensation, including the 13th month’s salary and vacation pay. This FGTS payment is a type of dismissal insurance with which all the employers that hire employees under the CLT regime need to comply. This FGTS amount will be available for the CLT worker after the termination of his contract depending on the type of dismissal (only in case of dismissal without a fair cause or due to other circumstances that are not related to the work relationship). Also, in case of dismissal without fair cause, the employer must pay a penalty of 50% of all the FGTS amounts deposited during the period of employment.

Moreover, the company also must withhold IRRF on amounts paid to employees and self-employed workers. Brazilian income tax rates range from 7.5% to 27.5% according to the total payment amount; tax is deducted from the employee’s or individual contractor’s wages but paid over to the tax authorities by the company.

In addition to all labor tax payments mentioned above, employers are subject to federal tax obligations that must be submitted regularly to the Brazilian Social Security and Tax Authorities, such as:

- CAGED (General Registry of Employment and Unemployment)—monthly submission of the number of hirings, dismissals, and current employees

- GFIP (FGTS Collection and Social Security Information Form)—monthly submission of information on employees’ and self-employed workers’ compensation, INSS and FGTS calculation basis, INSS withheld on payroll, among other significant data on FGTS and INSS

- RAIS (annual information regarding employment relationship)—annual submission of employees’ information

- DIRF (Withholding Income Tax Return)—annual withholding income tax return containing detailed information on amounts withheld and whom the amounts were withheld from

- PAT (Worker’s Food Allowance Program)—a form that the company needs to fill in once and keep updated with information on food allowances granted to its employees

If a company fails to submit the necessary obligations mentioned above on the due date, it will be subject to penalties according to Brazilian law. For example, if the company does not submit the PAT form, all the amounts paid to employees as food allowance will be considered to be part of their salaries; consequently, they will be treated as the basis for INSS, FGTS, and IRRF, resulting in the possibility of significant penalties for nonpayment of those figures.

Despite all of the unions’ and labor associations’ complaints, a law that allows companies to outsource services was recently approved in Congress. This law determines that a company can outsource all kinds of services. Until that law was passed, Brazil did not have legislation that allowed outsourcing. A Supreme Labor Court precedent established some premises for outsourcing; for example, the outsourcing would be only allowed regarding services that were not related to the core business of a corporation.

The problem with that precedent was the confusion that surrounds the meaning of core business. This concept is challenged every day in Brazilian Labor Court. Due to the complexity of some businesses, many companies have difficulty defining which services are defined as core and which are not. From now onward, it is expected that companies will have fewer legal problems regarding outsourced services.

The views reflected in this article are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the global EY organization or its member firms.

Editor’s note: Part II of this article will explore Brazil’s eSocial platform, present global payroll highlights for companies operating in Brazil, and provide an overview of the complex Brazilian payroll, labor, and accessory obligation scenario.

Ricardo Winter is a manager of EY’s People Advisory Services in Brazil with nine years of work experience in labor law and social security areas. He has experience in a wide range of HR and payroll projects in different industries where his focus is on reviewing processes, gap analysis, internal controls, business compliance, risk assessment, corporate policies, and procedures regarding compliance with labor and social security legislation. He also has international experience in several global employment tax projects in EY Chile.

Ricardo Winter is a manager of EY’s People Advisory Services in Brazil with nine years of work experience in labor law and social security areas. He has experience in a wide range of HR and payroll projects in different industries where his focus is on reviewing processes, gap analysis, internal controls, business compliance, risk assessment, corporate policies, and procedures regarding compliance with labor and social security legislation. He also has international experience in several global employment tax projects in EY Chile.

Paula Abreu works in Labor and Social Security Law at EY’s Rio de Janeiro office. She has been working with labor and social security projects and analysis for more than six years and has experience in audit and consulting for companies from different industries. Abreu works with labor and social security procedures for the purposes of compliance, advisory, and mergers and acquisitions for national and multinational clients. She also participates on projects helping companies adapt to eSocial (new Brazilian ancillary obligation).

Paula Abreu works in Labor and Social Security Law at EY’s Rio de Janeiro office. She has been working with labor and social security projects and analysis for more than six years and has experience in audit and consulting for companies from different industries. Abreu works with labor and social security procedures for the purposes of compliance, advisory, and mergers and acquisitions for national and multinational clients. She also participates on projects helping companies adapt to eSocial (new Brazilian ancillary obligation).